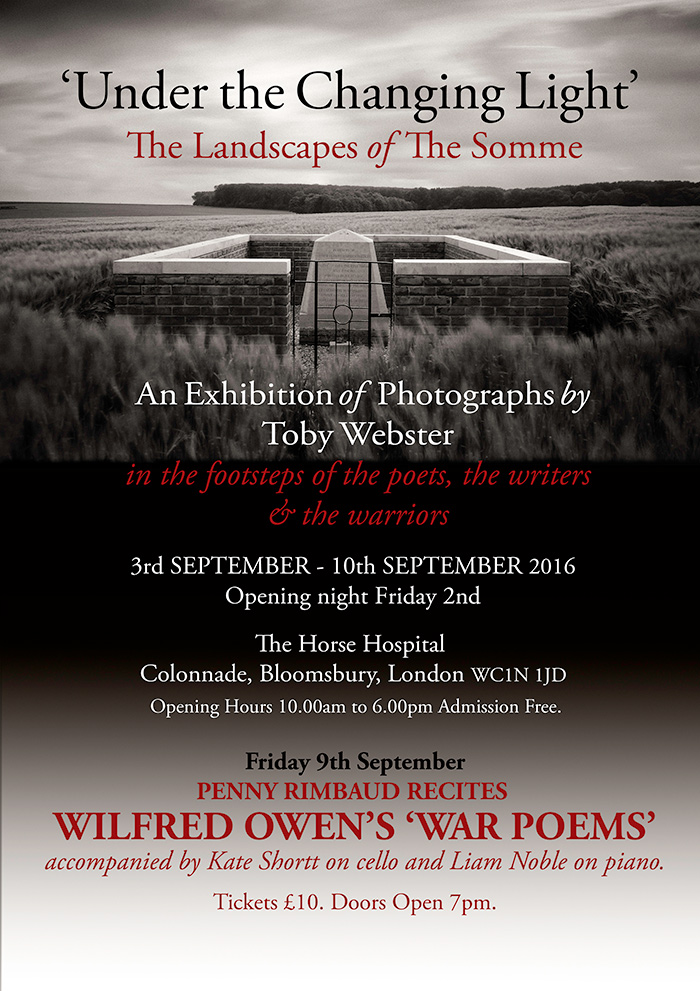

TOBY WEBSTER: UNDER THE CHANGING LIGHT

.

EXHIBITION: SAT 3rd Sept – SAT 10th Sept, MON – SAT, 12 – 6pm

.

PRIVATE VIEW: FRI 2nd Sept, 7pm

.

Fri 9th Sept, 7pm: Penny Rimbaud recites the works of Wilfred Owen with Kate Shortt/cello and Liam Noble/piano

(click here for more information)

.

"The trees are very high in the wan signal beam, to whose slow gyrations their wounded boughs seem as malignant limbs manoeuvring for advantage. The trees of the wood beware each other, and under each a man sitting, their seemly faces as carved in a sardonix stone. As undiademed princes turn their gracious profiles in a hidden seal, so did these appear, under the changing light" - David Jones, from "In Parenthesis"

Always drawn by echoes from a childhood steeped in the images of almost featureless landscapes characterised primarily by the meeting of shattered, grey earth with relentlessly open sky, pierced only by the stark, pleading boughs of leafless trees, I didn't actually formally visit the battlefield until a dozen or so years ago, and found myself strangely shocked that names such as Mametz, Delville Wood, Bazentin and Beaumont-Hamel represented fields, woods and villages that actually exist in a contemporary reality. It is difficult not to be deeply moved by such a collision of the tangible with the recall of long mythologised mental imagery. I found myself drawn time and again to this gentle landscape, and as I learned more of the fine details of what had taken place here, so I discovered that it was surprisingly easy to find and walk in the footsteps of those who had written the accounts. So the seed of this project was sown.

It is a landscape that today bears a surprising resemblance to its pre-war appearance. The infamous woods have regrown within their original boundaries, and a century later the trees stand tall beneath their dense canopies. The roads, tracks and byways run along their former paths, though there are fewer of them – the pre-war population was significantly higher than it is now, and the rebuilt villages remain smaller than their predecessors. It is now, as it was then, an intensive agricultural landscape dominated by the sugar beet industry, though the beet factories and the network of light railways that served them prior to the war and again in the 1930s and 40s are long gone. It is quiet and still, the brickwork of the villages much softened by the 8 or 9 decades that have passed since they were first raised, stark above the then empty battlefield, but still dour and inward-looking, the windowless backs of the barns turned towards the roads. But the light is open, and soft, and often fine, and the roll of the chalk downs is subtly attractive to the photographer.

It is a landscape that would, were it not for the cemeteries that punctuate its every aspect, bear no hint to the casual passer by of what happened there such a short time ago. But look a little deeper, and the evidence is everywhere. The interiors of the woods still bear traces, sometimes vivid, of trenchlines and shellholes, and the eye, when it becomes accustomed, sees scattered everywhere the red-rusty-oxide lumps, fragments and shards of iron. Unexploded shells, thousands of them, are dragged up each year by the plough, and left at the side of roads for the collection teams. Sometimes there is the sinisterly fascinating, faceted egg of a hand grenade, or the sleek shape of a bullet. More rarely there might be something personal, the green copper that signifies a cap or shoulder badge, a rusty water bottle, or even, for there are many there, just under the surface, a shard of yellowing human bone. Scratch the surface of this landscape, and it quickly reveals the horror that lies beneath.

Between 2013 and now, I have visited the battlefield at every opportunity, retracing with my camera the footsteps of Graves, Jones, Manning and the others. Sometimes the landscape yields a photograph relatively willingly, other times it is stubborn and taunting, or the light falls away and the sky cracks apart. Upon a few I have had to admit defeat, for, although I know that I am standing exactly where the writer stood, the landscape in front of me now offers nothing, or is marred by pylons or ugly new buildings. But on the whole the Somme has been kind, sometimes uncannily so. There have indeed been moments when I have felt that surely fate, or the ghosts, perhaps even the elusive 'Queen of the Woods', has taken me by the hand and quietly set me in the right direction. I hope only that my efforts have repayed such generosity.

TOBY WEBSTER Born in Essex, Toby attended an Art Foundation course at a local Technical College in the late 1970s, where he developed his interest, held since his grandfather gifted him a Pentax SLR camera as a teenager, in photography. Webster won a place at Nottingham & Trent Polytechnic on their highly regarded Photography Course, where tutors included on occasion such notable luminaries as Fay Godwin. In the late 1970s and early 80s he documented the last of London’s enclosed docks, atmospheric and abandoned places then, and he has subsequently engaged in personal projects to document the now empty landscapes of East Anglia’s many former wartime bomber bases, and for many years he has been photographing the remains of Cornwall’s tin mining industry.