Walerian Borowczyk - Posters and Lithography

PRIVATE VIEW: Friday 23rd May, 7pm

EXHIBITION: Sat 24th May – Sat 14th June, Mon – Sat, 12 – 6pm

Prior to establishing himself as a filmmaker during the late 1950s, Walerian Borowczyk (1923 - 2006) was best known in Poland for his graphic work, which included satirical drawings, lithographic cycles and film posters.

This exhibition presents a selection of Borowczyk’s work from this period.

Born in Kwilcz, a village near Poznań in 1923, Borowczyk studied painting and sculpture at the Krakow Academy of Fine Art between 1946 and 1951. Borowczyk painted in the studio of Zbigniew Pronaszko alongside Jan Tarasin and Jerzy Tchórzewski. Pronaszko painted in the Colourist, or Kapist style.

Kapizm (a contraction of Komitet Paryski, or the Paris Committee) was represented by a group of French educated Polish painters who worked in the post-impressionist style.

Halfway through Borowczyk’s studies at Krakow, Socrealizm, Polish socialist realism, became the official aesthetic across the arts.

Like many of his peers in Krakow, Borowczyk supplemented his income by selling satirical drawings to weekly journals, most notably Szpilki (Pins), edited by Eryk Lipiński .

Borowczyk took his cue from the nineteenth century French artist, Honoré Daumier. The target of his drawings was, for the most part, Western imperialism, typified by the then American President, Harry S. Truman.

In 1953, Borowczyk was awarded the Polish National Prize for a lithographic cycle depicting the construction of the Nowa Huta district of Kraków. Completed in the year of Stalin’s death, Borowczyk presents building sites not as hives of activity but desolate, barren wastelands.

Arguably the most famous image from the cycle, Młody murarz w niedzielę (Bricklayer on a Sunday), depicts a work less concerned with the socialist cause than wearing a trilby and smoking a cigarette.

By the mid 1950s, socialist realism had been abandoned.

Having relocated to Warsaw, Borowczyk designed film posters. His emergence as a poster artist coincided with renaissance in Polish poster design. Freed from the constraints of socialist realism, Borowczyk and his peers developed a bold, sparse and witty approach towards image and text. Unlike Jan Lenica (with whom he would collaborate on a series of ground breaking short films at the end of the decade) Borowczyk did not develop a singular graphic style.

Much like in his films, Borowczyk sought forms through which to express ideas. Korzenie (Roots), a poster for the Mexican film, arranges images of scenes from the film around the border not unlike an Orthodox icon. In his poster for Otakar Vavra’s Sobor w Konstancji (Jan Hus), three primitive demons stand in place of a king’s crown.

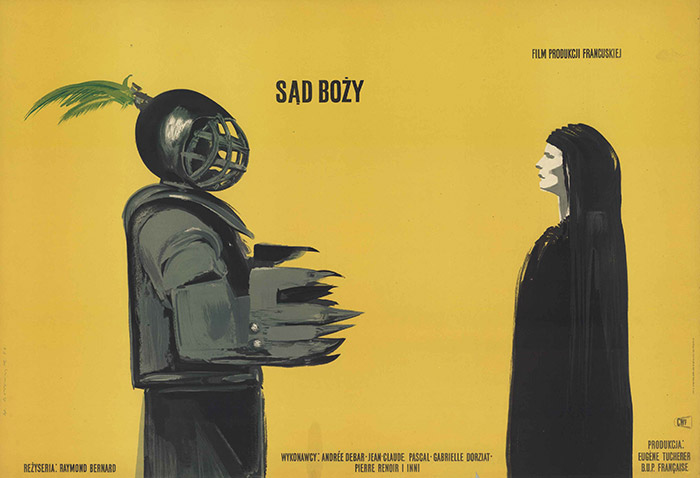

Other posters, like Sad bozy (Le Jugement de Dieu), which presents the confrontation of two figures (one in threatening armour) in profile, preempting many such scenes in both Borowczyk’s animations (Les Jeux des Anges, Theatre de M et Mme Kabal) and feature films (Goto, l’ile d’amour, Blanche).

Arguably Borowczyk’s most striking poster, for Bergman’s Seventh Seal (Siódma pieczęć), uses decalcomania in a surrealist manner not unlike Max Ernst.

Other posters, like Ja i moj Dziadek (My and my Grandfather) and Obcy Ludzie (Foreign People), make use of the cut out technique that would underpin Borowczyk’s first professional film (with Lenica), Byl sobie raz... (Once Upon a Time).

Often Borowczyk is characterized as a poster artist turned filmmaker. A keen amateur filmmaker since his youth, Borowczyk conceived of film posters as a medium related to film (particularly early cinema) in that both employ image and text as a means of expressing thoughts and feelings.

Borowczyk articulated these thoughts in a commentary (co-written by the art historian Szymon Bojko) for a short documentary on posters directed by Konstanty Gordon, Sztuka Ulicy (Street Art).

Not only do these prints offer a crucial insight into Borowczyk’s development both as a graphic artist and filmmaker, they also chart the changing landscape of Polish cultural life during the 1950s, from the darkest days of Stalinism through to the cultural renaissance during the early Gomulka years.

DB